Small Ship Expeditions in Antarctica

An expedition is more than a big adventure, it's a journey that changes you. The most meaningful adventures are the ones that tread lightly, leaving the wild places we visit as pristine as we found them.

As a Certified B Corporation™ and proudly Carbon Neutral, we believe adventure and responsibility go hand in hand. Our small ships feature cutting-edge technology, and every voyage blends adventure, conservation and education, so you can explore the world while helping to protect it.

Go where few have gone. Come back changed, ready to share your story.

Start your Adventure

Big Savings - Get up to 40% off Antarctica 2025-2026

South Georgia, Falklands & Antarctic Odyssey

South Georgia & Antarctic Odyssey featuring the South Sandwich Islands

Wild Antarctica featuring the Weddell Sea

Across the Antarctic Circle: Fly the Drake

Why Aurora? The Difference in the Details

Special Offers

Our Sustainability Commitment

Since the start, we have embraced a responsibility to inspire, educate and advocate for wild places across the globe, in order to inspire a global community of ambassadors for the planet. Aurora was one of the first operators to become members of both IAATO and AECO, and we are honoured to be a Certified B Corporation™. Not only do we care about reducing our footprint environmentally, we are taking real actions for the care of the planet.

What our guests are saying:

What the experts are saying:

Your Big Adventure Awaits

Every expedition is unique, shaped by weather, tides, ice, and our team’s deep local knowledge. Your Expedition Leader crafts each day for the best adventure. Want a glimpse of what it’s like? Browse a Voyage Log from a past journey. Each log is a beautifully crafted, day-to-day recap featuring highlights, photos, guest moments, and wildlife sightings. Browse now and start dreaming of your own big adventure.

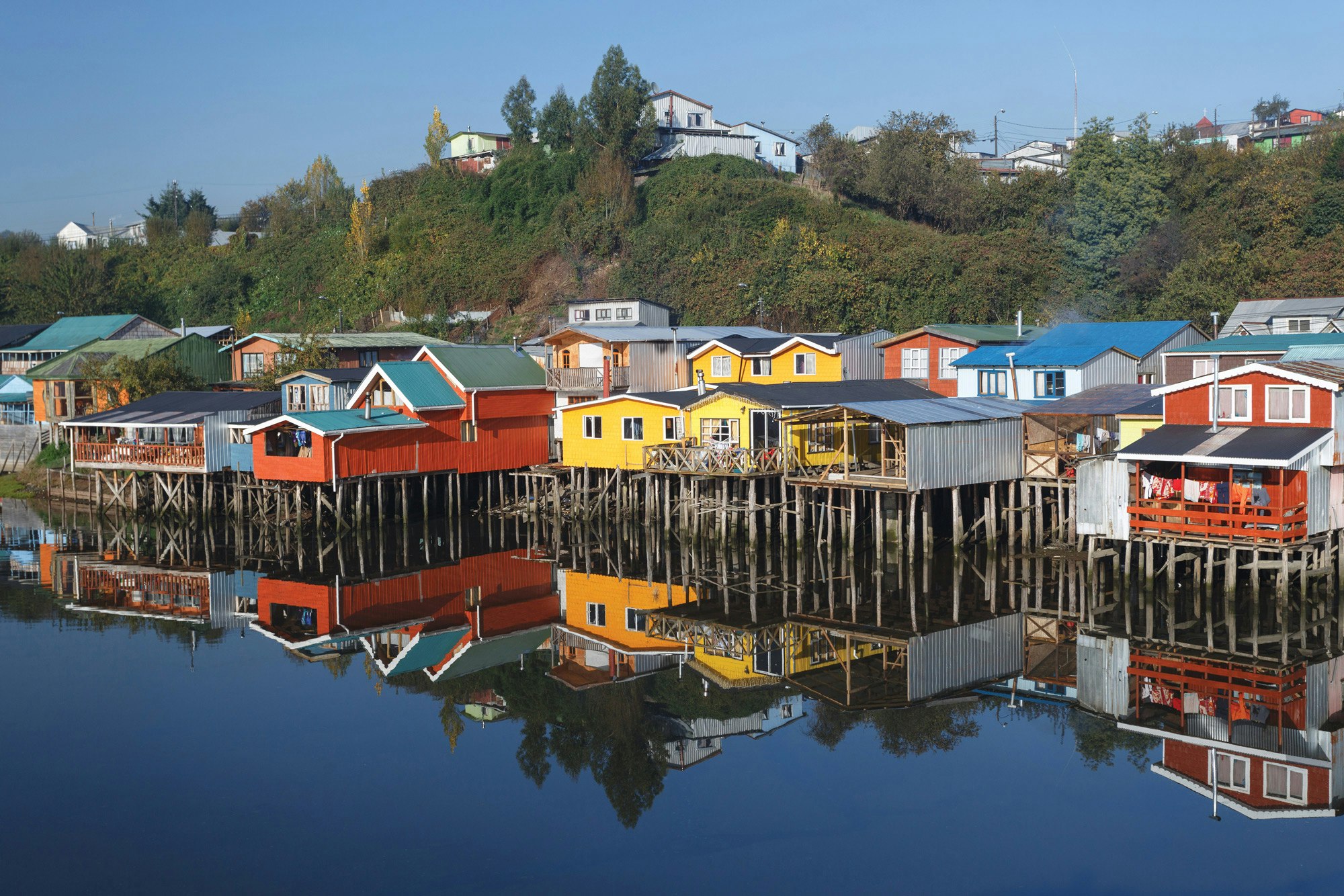

-in-Castro,-Chiloe-Island,-Patagonia,-Chile;-Shutterstock.jpg?language=en&auto=format&w={width}&fit=cover)